ALTER-EGO LIABILITY DEMYSTIFIED Don’t Put Your Personal Assets at Risk

By: Johnathan M. Hill, Esq.

If you’ve ever been told that setting up company, be it a corporation or a limited liability company (LLC), would insulate you from personal liability, what you got was only part of the story. While it’s true that one of the major benefits of forming a corporation or limited liability company is the ability to shield individual owners, members or shareholders from personal liability, legal protections limiting individual liability are not absolute. On the contrary, It’s possible for a claimant or creditor to “pierce the corporate veil” and get to your personal assets if you’re not careful about how you use the corporate form. When the walls between you and your company become too blurred, or break down completely, a court could consider you and your company to essentially be one-in-the-same, or, stated differently, that your company exists solely for purposes of serving as your “alter-ego.” This article seeks to provide a layman’s understanding of alter-ego liability, and provide a roadmap for minimizing the possibility that your personal assets could be at risk under such a theory.

As a starting point, it’s important to understand the legal framework behind alter-ego liability, which requires us to know something about “corporate personhood” (yes, corporations are people too). Dating back to 1819, and the landmark case of Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. 518 (1819), the U.S. Supreme Court recognized a corporation as having the same rights as a natural person to contract and to enforce contracts. As Chief Justice Marshall famously said:

A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law. Being the mere creature of law, it possesses only those properties which the charter of its creation confers upon it, either expressly, or as incidental to its very existence. These are such as are supposed best calculated to effect the object for which it was created. Among the most important are immortality, and, if the expression may be allowed, individuality; properties, by which a perpetual succession of many persons are considered as the same, and may act as a single individual.

Relevant to our discussion about alter-ego liability, this notion of corporate personhood is important for this reason: when individual owners, members and shareholders direct the actions of the separate corporate person – which is to say, they act as agents of the company – no individual liability should attach for actions they take on behalf of the company. But, where the corporate person breaks down – which is to say, the individual or individuals who control the company disregard the corporate form, or abuse it, to such a degree that there is really no appreciable difference between the individual’s actions and the company’s actions – then it’s possible for personal liability to attach to owners, member or shareholders.

Alter-ego liability is a question of state law, so, it’s important that you speak to a local attorney to figure out what courts in your state have said about alter-ego liability, and what steps you can take to protect yourself. In Georgia, where I practice, courts have said this:

To prevail based upon this theory [of alter ego liability], it is necessary to show that the shareholders disregarded the corporate entity and made it a mere instrumentality for the transaction of their own affairs; that there is such unity of interest and ownership that the separate personalities of the corporation and the owners no longer exist. The concept of piercing the corporate veil is applied in Georgia to remedy injustices which arise where a party has over extended his privilege in the use of a corporate entity in order to defeat justice, perpetuate fraud or to evade contractual or tort responsibility. Because the cardinal rule of corporate law is that a corporation possesses a legal existence separate and apart from that of its officers and shareholders, the mere operation of corporate business does not render one personally liable for corporate acts. Sole ownership of a corporation by one person or another corporation is not a factor, and neither is the fact that the sole owner uses and controls it to promote his ends. There must be some evidence of abuse of the corporate form.

Dews v. Ratterree, 246 Ga. App. 324, 327 (Ga. Ct. App. 2000).

In California, while there is not fixed test for determining alter-ego liability, courts there work with a similar set of elements as described in the Georgia rule above. California’s general rule can be stated as follows:

Before a corporation’s acts and obligations can be legally recognized as those of a particular person, and vice versa, it must be made to appear that the corporation is not only influenced and governed by that person, but that there is such a unity of interest and ownership that the individuality, or separateness, of such person and corporation has ceased, and that the facts are such that an adherence to the fiction of the separate existence of the corporation would, under the particular circumstances, sanction a fraud or promote injustice.

Talbot v. Fresno-Pacific Corp., 181 Cal. App. 2d 425, 431 (Cal. App. 4th Dist. 1960).

An often-cited case in California which explains alter-ego liability is Associated Vendors, Inc. v. Oakland Meat Co., 210 Cal. App. 2d 825, 836 (Cal. App. 1st Dist. 1962). In Associated Vendors, the Court described a panoply of different factors to consider in determining whether a sufficient “unity of interest” exists between the corporation and the individual to pierce the corporate veil in establishing alter-ego liability. Although none of the Associated Vendors factors are controlling (they need to be weighed together), they offer useful guidance on what business owners can do to minimize the risk that their personal assets could come into the crosshairs for liability under an alter-ego theory of recovery.

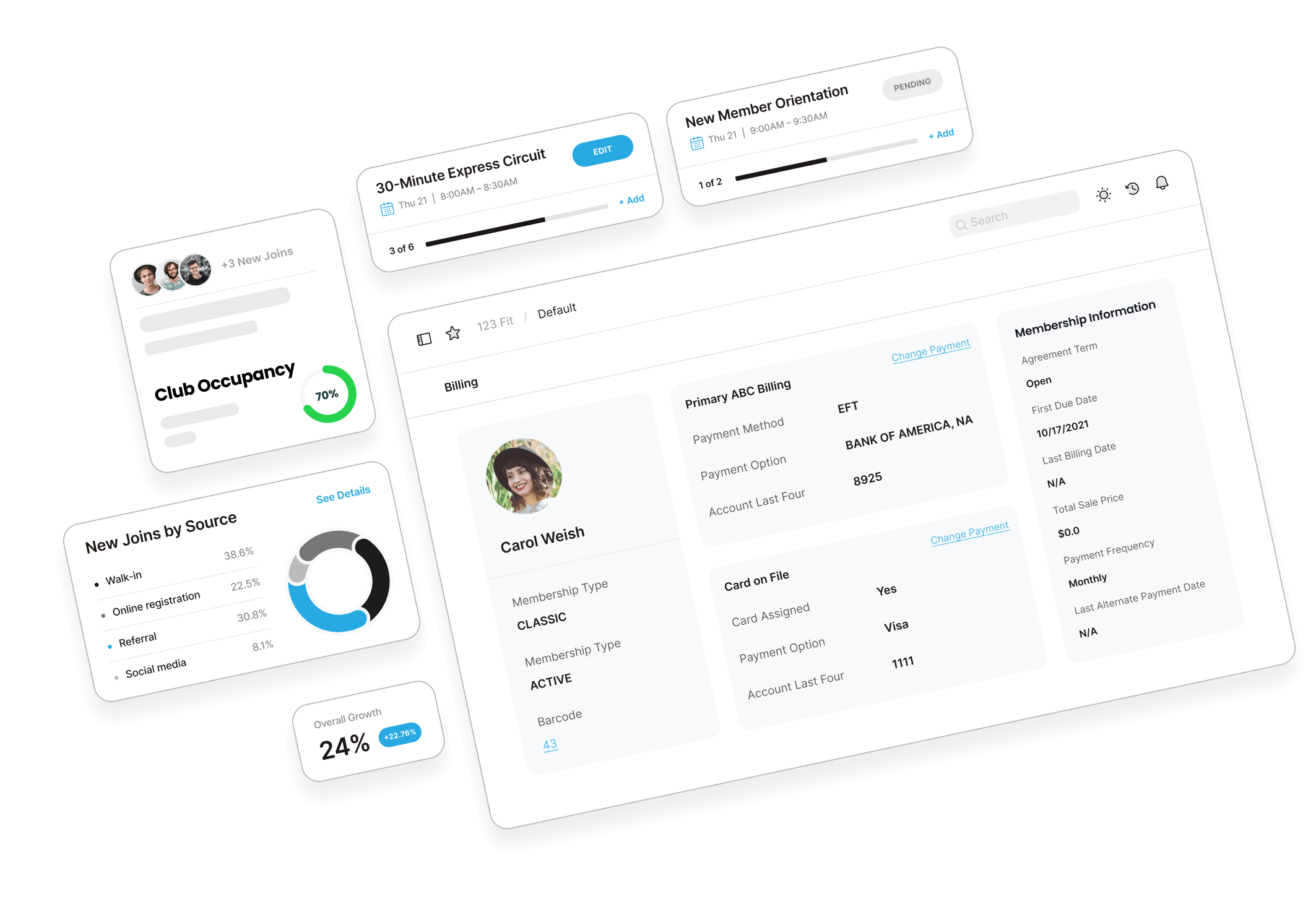

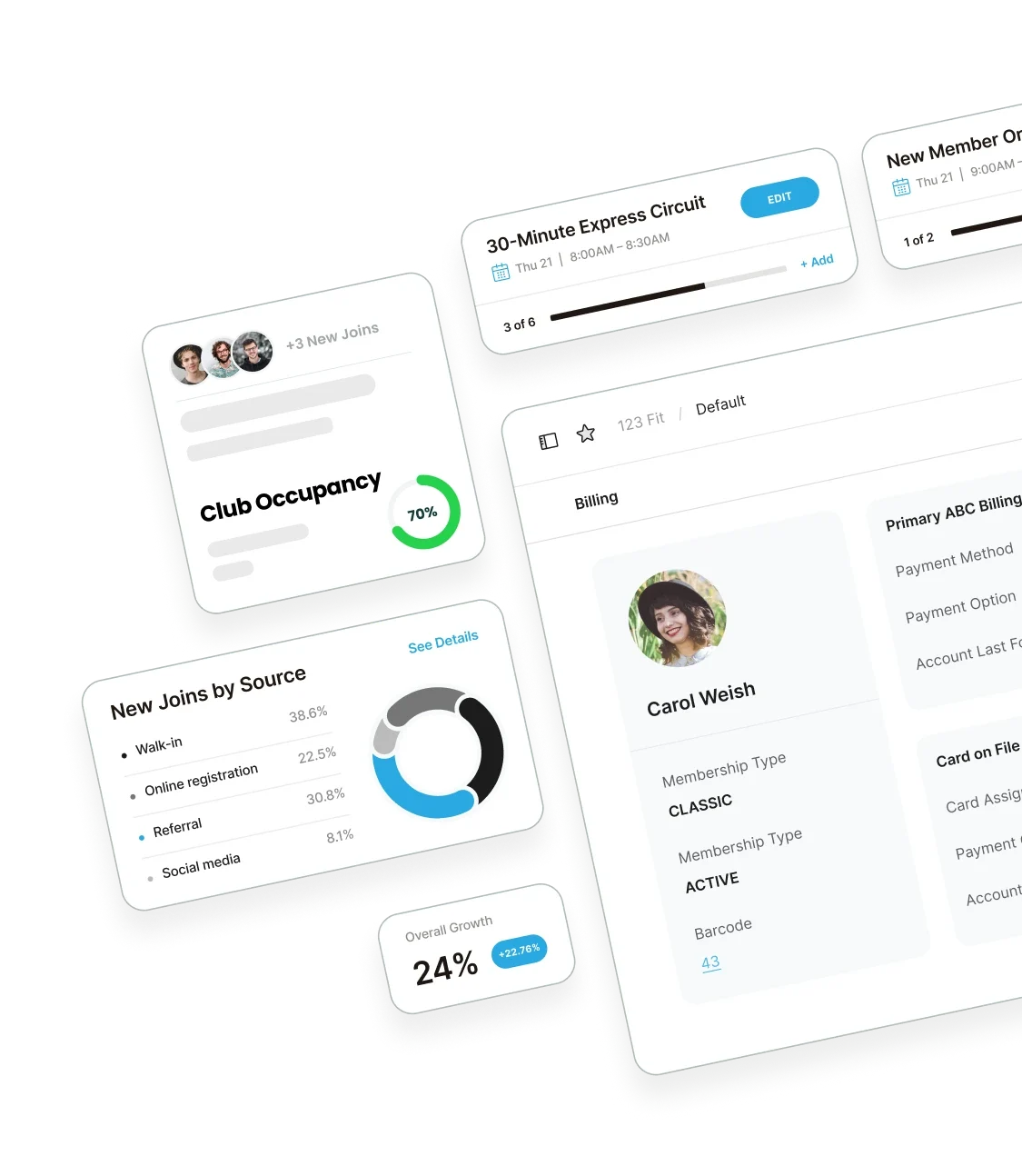

If you own a gym or another fitness-related business (either alone or with partners), these are the questions you should ask yourself because they are the same questions that will guide a court’s analysis on an alter-ego theory of personal liability:

- Have you commingled funds or other assets; have you failed to segregate funds to separate entities; have company monies been diverted for uses that do not benefit the company?

- Are you treating the company’s assets as your own?

- Have you failed to get the appropriate authorization to issue or subscribe to stock?

- Have you held yourself out as being personally liable for the company’s debts?

- Have you failed to maintain minutes and/or other corporate records? Is there confusion about which corporate records apply to which entities?

- Are the equitable owners of more than one company the same?

- Is all of the company’s stock owned by one person or one family?

- Is there inadequate documentation to back up the allocation of company funds? Do any expenditures of company monies fail to benefit the company?

- Is the ownership, or the officers and directors, for two or more companies the same?

- Is a home office used as the company’s corporate office? Is the same office or business location used as the office for more than one company?

- Are employees shared between companies?

- Has the company been inadequately funded? Has it been undercapitalized?

- Has there been a failure to follow legal formalities, like incorporating or filing annual reports?

- Has the company failed to maintain an arm’s length relationship with other companies (Does the company lack contracts to support its business dealings with other third parties)?

- Has the company failed to hold shareholder and director meetings?

- Has the company failed to pay taxes, including income and payroll taxes?

- Have assets been concentrated in one company and liabilities in another?

- Has a company been formed to assume the liabilities of another person or entity?

- Has the company’s ownership, management and/or financial interests been concealed or misrepresented?

- Has the company’s identity been used to procure labor, services or merchandise on behalf of another company?

- Have company funds been diverted to owners or stockholders to the detriment of creditors?

- Has the company been used as a subterfuge for illegal activity?

If you answered “yes” to any of the questions above, alter-ego liability could exist. It’s worth noting that alter-ego liability is one way to pierce the corporate veil, but there are others. This article is merely an overview of alter-ego liability, and is intended to help you avoid common mistakes made by business owners (particularly those in closely-held corporation or single-owner companies). As with all questions related to your and your business’s legal rights and duties, it’s best to consult with an attorney skilled in this area of law.

Jonathan M. Hill is the Managing Partner with the Hill Law Group, LLC, a firm specializing in the representation of health clubs, fitness studios and personal training companies throughout the U.S. For more information about Hill Law Group, LLC visit www.hill-law-group.com, or contact Jonathan at jhill@hill-law-group.com